- Home

- Benjamin Taylor

Here We Are Page 3

Here We Are Read online

Page 3

“Being denounced by the Anti-Defamation League was nothing compared to the firestorm Portnoy raised. No less a figure than Professor Gershom Scholem said it was worse than The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. The book had too much impact. I was not Norman Mailer. Trouble was not my middle name. The book made me too famous, determined too much of my life to come. People don’t believe me when I say this, but I wish I’d just let the individual chapters stand in those magazines. I could have escaped the burden of being a scandal. I could have escaped having my mother in some torment saying, ‘Philip, darling, are you—anti-Semitic? Because that’s what we hear.’”

Silence, exile, cunning and the three-hour writing rule, Philip used to say of his work ethic. “Same old story. You can’t guard a hundred percent. Fifty’s a good goal.” He on whom the trap of fame had snapped shut when he was thirty-six said the only way forward was to pay no attention. “The writer,” he told me, “wants intelligent recognition. Not to be disappointed, let down—insulted. And what if he gets recognition? There’s always the source of disappointment lurking somewhere. Which means everywhere.”

* * *

—

A winter’s evening in the early naughts: “I must warn you, Ben. You’ve got a face that shows too much.” Though the conversation was fluent, we didn’t know each other very well yet. “I eat in dumps,” he’d told me. It was true. That night’s venue was an undistinguished Italian restaurant in his neighborhood. I’ll simply call it, as he did, The Meatball. When Philip was depressed he’d want to go there. I quickly learned to recognize any proposal to dine at The Meatball as an SOS. Perhaps the “too much” showing on my face that night was worry.

The problem was that he was waging love on two fronts at once. Or was it three? A natural bachelor, as I say. More frankly, a law unto himself. “No punishment is too harsh,” he told me, “for the demiurge who thought up fidelity.” That Philip was both an ardent lover and a sexual anarch was the inner dynamism of his life as well as his art. “Monogamy would not have been in me had I lived in the era of Cotton Mather. As it was, I lived in the era of Screw magazine and Linda Lovelace.”

But if monogamy was anathema to him so was enduring the opprobrium the polyamorous suffer. In My Life as a Man the hero, Peter Tarnopol, speaks for his maker when he says: “I may not be well suited for the notoriety that attends the publication of an unabashed and unexpurgated history of one’s erotic endeavors. As the history itself will testify, I happen to be no more immune to shame or built for public exposure than the next burgher with shades on his bedroom windows and a latch on the bathroom door—indeed, maybe what the whole history signifies is that I am sensitive to nothing in all the world as I am to my moral reputation.”

Torment about rectitude plagued him as acutely as any itch in the loins. That a man who’d written those books and led that life should be so primly worried about what people were saying struck me as funny. It may, from time to time, have been amusement at his expense that was registering on my face.

“Philip, I’m going to introduce you to a better class of restaurant.”

As a novelist, he believed that the truth was compounded of perspectives and partial understandings. After the early books he shunned omniscience. “The fact remains that getting people right is not what living is all about anyway,” he writes in American Pastoral. “It’s getting them wrong that is living, getting them wrong and wrong and wrong and then, on careful reconsideration, getting them wrong again. That’s how we know we’re alive: we’re wrong.” And in Sabbath’s Theater: “If what you think happened happens to not ever match up with what somebody else thinks happened, how could you say you know even that? Everybody got everything wrong.”

Yet he was not similarly skeptical about his own self-understanding in real life—“the unwritten world,” as he preferred to call it. Bluntly, Philip was allergic to the idea that he could have been at fault in either of his unhappy marriages and to the idea that the party of the other part might, in both cases, have had grievances worth considering. His own angle of vision was complete and unfailing. Other accounts were distortions. This explains so much about him: for example, his vexed search for a biographer, which dragged on for years. He was looking not for a Boswell to fix him to the page but for a ventriloquist’s dummy to sit in his lap. It was really an impossible quest. He wanted someone first-rate he could entirely bend to his point of view. What he got in Blake Bailey, the eventual official biographer, was someone more independent-minded, indeed more formidable, than Philip could calmly resign himself to. “Two things await me,” he used to say, “death and my biographer. I don’t know which is more to be feared.”

* * *

—

About Mary McCarthy he said: “She had a very strong need to be right.”

“You too?”

“To prevail.”

It was certainly true that he never grew dispassionate about injuries from the past, or about the splendid sufficiency of his own point of view on them. In any conflict he needed, in the telling, to have morally prevailed. At another of our early dinners (in a restaurant of my choosing) he told me, as he sooner or later told everyone, the lurid tale of his first marriage. It was always a matter of evening the score with the late Margaret Martinson Williams Roth, a divorced mother of two when he met her, whose children the courts rotated among relatives. Little could I have known on this first hearing that I’d listen to the story a hundred times more. Despite her death she needed further—no, endless— pulverization.

They had married early in 1959 after she faked the results of a pregnancy test by paying a pregnant woman in Tompkins Square Park to furnish the urine sample. “Her art of fiction,” as Tarnopol says of Maggie’s counterpart, Maureen. “‘Creativity’ gone awry.” She’d already threatened suicide. Guilty-hearted good boy, believing the hoax, Philip accepted her umpteenth proposal of marriage.

“We’ll be happy as kings!” Maggie crowed, just as Maureen does in My Life as a Man, and declared that as Mrs. Roth she’d be more than willing to have an abortion. Which she, who hadn’t been pregnant in the first place, promptly went off and pretended to do. She spent the afternoon in a Times Square movie house watching two features of Susan Hayward in I Want to Live!, then came home to East Tenth Street, disheveled and reporting on how horrible the supposed ordeal had been, and put herself to bed.

Such were the two lies upon which their marriage was founded. It would not be dissolved till her death ten years later in a car crash on one of the transverses of Central Park.

That evening at dinner I jumped in my chair when Philip banged his hand on the table—banged as if Maggie’s deceptions had happened last month, not most of a lifetime ago. “I found out the whole outlandish truth when she confessed it following her suicide attempt in 1962. The dedicatee of Letting Go and model for Martha Reganhart”—the novel’s scrappy, lively heroine and best thing in the book—“was nemesis itself and the vandal of my young manhood. The goal thereafter was never to be hoodwinked again.”

“How about leaving her to heaven, Philip?”

But he couldn’t. “A writer needs to be driven round the bend,” he told me. “Needs his poisons. He battens on them.” The death of one or the other party was, Philip felt, the only possible conclusion to their unholy union. But he knew he owed her. “Without doubt she was my worst enemy ever,” he writes in The Facts, “but, alas, she was also nothing less than the greatest creative writing teacher of them all, specialist par excellence in the aesthetics of extremist fiction.”

Then, suddenly, she was dead. “All I had done the night before was to close my eyes and go to sleep, and now everything was over.” When on that May morning in 1968 the news of the fatal wreck came, he believed it a sinister ploy cooked up by her lawyer to get him to say something usable in court. The convenience of her death seemed too glaring a deus ex machina, more peremptory even than the death of Lucy Nelson in Wh

en She Was Good, his novel from a year earlier, whose heroine is likewise based on Maggie and whose death is eerily predictive of hers. “Every writer,” he told me more than once, “has the experience of imagining things that then come to pass. But my tormented heroine’s violent death one year before Maggie’s seemed too, too—”

“Too on the nose, as the young say?”

“Too on the nose.”

After her funeral, Philip went to what may or may not have been the spot where she died, lifted his face to the clement sun and rejoiced in his improbable freedom.

That we owe a lot to our misadventures is a key to his books. In My Life as a Man—that “autofiction,” to use the fashionable term, of the years with Maggie—there’s a poet in residence at Quahsay, the Yaddo-like artists’ colony to which Peter Tarnopol has retreated, who drinks everything on the premises, including the vanilla extract, before being carted off to AA. “Ah, don’t worry,” she calls from the departing car, “if it wasn’t for my mistakes I’d still be back on the front porch in Boise.”

First Martha Reganhart. Then Lucy Nelson. Then Maureen Tarnopol. Maggie had been a powerful spur to Philip’s artistry. She and her family were his education in the small-town ghastliness on which American naturalism has prospered: penury, domestic violence, alcoholism, teenage pregnancy, incarceration. The perky square-jawed blonde whom the University of Chicago instructor in the glen-plaid suit had so blithely engaged in conversation in the doorway of a Fifty-Seventh Street bookshop seemed a veteran of harder knocks than the Weequahic section could provide knowledge of. She was real life, the deep America. Theodore Dreiser and Sherwood Anderson would have agreed. But they would not have mistaken her for harmless. She was Philip’s bighearted mistake. He never calmed down about their connubial hell. He still felt the heat of it. “Good Intentions Paving Company!” he’d sometimes pick up the phone and say—in old age, when all but medical battles were behind him.

To put a little something on Maggie’s side of the scale, one might observe that she liked being lied to no better than other wives do. Good though his intentions were, Philip had to roam. And fib about it. “Every knuckle dragger’s an Olivier,” he used to say, “when required to deceive his wife. The wisdom of it is cumulative, handed down through the generations.”

“Through the generations? You think your father strayed?”

“No, no. But in the fullness of time he had sons to atone for his monogamy.” Yet Philip made a poor Don Juan. He was too apt to fall in love. Then, having fallen in love, he needed to escape from the presumed monogamy love entailed, needed to fall in love again. This was a lifelong pattern and furnishes reason to regard Maggie, as I say, a bit more sympathetically than Roth loyalists do. Of course she was driven to jealous stratagems—Philip was undomesticatable. She raged with cause, turning up at his classroom to berate him and worse. She was a street fighter from nowhere possessed of a marital ideal with which her husband did not concur. The unholiness of their bond had as much to do with his profligacy as her possessiveness. His determination to make himself the nice-boy victim of a Medea or a Hedda Gabler or some other succubus remains hard to credit. She felt betrayed early and often. (One evening over dinner I used the term “philanderer.” “We’re all better off without that word,” he snapped. It may have been his least favorite in the language. Whereas the word he loved best from childhood was “away.”)

Driving from Italy to France with her during the infernal Guggenheim year of 1959, Philip had nearly lost control of their car on a steep road when Maggie grabbed the wheel. Some other woman was the likely cause of the argument; other women were what she was always in a rage about. Philip hypothesized that the man who was with her that night in Central Park was getting the same treatment at the wheel. He suffered a minor head injury, she a fatal one. “My emancipator,” Philip called him.

CHAPTER FOUR

HOUSEKEEPING IN AMERICA

250 Melius Road, Warren, Connecticut

It is 2008 or 2009, a crisp autumn day. We’ve gone for a walk in Theodore Roosevelt Park behind the Museum of Natural History. A monument with the names of America’s Nobel laureates has been erected here, perhaps a thousand yards from Philip’s doorstep. As we examine the monument, a gnarled woman approaches. “Looking for your name? It’s not there!” she says to him and darts off like a shot.

The Nobel drama became increasingly tedious as the years wore on. Each October came the rumor: He was tipped to win. Ladbrokes had him at three to one. A couple of times he even defied fate by saying he’d cover my expenses to Stockholm. We tried to talk about other things. Then, after the disappointing announcement, I’d recite the honor roll of those overlooked: Henry James, Tolstoy, Proust, others. But it gnawed Philip to be denied that particular laurel. He took to calling it the Anybody-But-Roth Prize. October was the cruelest month.

* * *

—

Your path has been your own,” he told me, which meant a great deal or nothing at all. I decided on the former. He liked the vigorous attitudes I brought to my life. “You’ve found a good mean—equal disdain for boasting and false modesty.” He called me a homemade cosmopolitan, the nicest compliment I’ve ever received. After my brother’s sudden death in a snowmobiling accident in 2006, he phoned every day for weeks, then months. He’d say: “It eases my mind to hear you.” When at last I could laugh again he said: “That’s what I’ve been waiting for.” He was the chosen parent of my middle age. Ours was an elective genealogy, “a genealogy that isn’t genetic,” as he calls it in I Married a Communist—leading to the orphanhood that is total, “when you’re out there in this thing all alone.”

Philip’s inner life was gargantuan. Insatiable emotional appetites—for rage as for love—led into paths where he seethed with loathing or desire. “There’s too much of you, Philip. All your emotions are outsize.”

“I’ve written in order not to die of them.” To be stuck with the untransformed unforeseen, all the terrible contingencies, “sans language, shape, structure, meaning—sans the unities, the catharsis,” as he puts it in The Human Stain, would have burned him up.

He never stopped marveling at how contingently a fate is made. It was, for him, what was most basic to storytelling: the happenstance that, in retrospect, turns epic. The owl of Minerva takes flight and all that might not have been becomes all that has incontrovertibly happened, a shimmering thread the Fates wove.

We’re attending Russ Murdoch’s annual pig roast near Philip’s house in Warren. The sight of the cooked animal—nose, eyeballs, hooves, corkscrew tail—turns my legs to jelly.

“You look peaked,” Philip says. “Go sit down. With your back to the beast. I’ll bring you a little of that potato salad.”

I shake my head, put a hand to my mouth, puff out my cheeks.

“Maybe just some carbonated water?”

I nod weakly.

“Breathe through your mouth,” he advises, exactly as my old man would have done. Probably his too. We’ve made a list of fatherisms: “Buckle down, Winsocki.” “Like it or lump it.” “You’re pressing your luck.” “Who do you think we are, the Rockefellers?” “You’re going to put out an eye with that thing.” “Don’t get your bowels in an uproar.” “I’ll take it up with General MacArthur.” “Ask your mother.” “I’ve been very patient with you.” “Can I make it any clearer?” “You’re on thin ice.” “You’ve got more hours in that bathroom than Rickenbacker had in the air.” “You’ll be saying you’re sorry in a minute.” “Don’t make a federal case out of it.” By way of encouragement: “Keep your pecker up.” In response to a request for extra money: “Soon as my rich uncle gets off the poor farm.” When a new appliance was being assembled: “Don’t force it!” Sometimes just “Sez you” or “Malarky.” Sometimes, and unanswerably: “Get with the program.”

“My father,” I said, “would announce, when consuming any spicy dish: ‘This is as hot a

s Aunt Blanche!’ My brother and I begged to know more about her and this led to quite a saga. She’d been the madam of a joy house in New Orleans and after that a United States senator. One day soon she’d be swooping down to pay us a visit in Fort Worth. I pictured a Mae West type filling up the living room and wondered just how hot Aunt Blanche was.”

“Were you a puzzle to him?”

“He wondered how he’d engendered me, yes. I remember the look on his face when he asked who’d won the softball game and I told him I thought it had been a tie. The most scathing fatherism at our house was chagrined silence after a remark of mine like that.”

“Herman’s best fatherisms were authoritatively delivered pearls of wisdom based on fragmentary or dubious information. I remember V-J Day at Bradley Beach: the huzzahs and tears and a conga line forming up on the boardwalk. And Dad saying, ‘From here on, boys, we’re going atomic!’”

The only real opponent Philip faced in young manhood was his father, and it was opposition of the most loving kind. Herman feared the larger world, feared what it could do to his wide-eyed, unwary boys. He particularly feared what sex could do to them. I don’t think there were more than a dozen real quarrels under that roof, the majority of them having to do with Philip’s need for independence. The Roths were a sparkling example of what family life could be: the American dream coming true. The ballast was right. The happy childhood Philip wrote of had not been manufactured ex post facto. It was real. Accidental but real.

As for his mother, he reports in Patrimony that Bess Roth single-handedly established “a first-class domestic-management and mothering company back in 1927,” the year of Sandy’s birth, raising “housekeeping in America to a great art.”

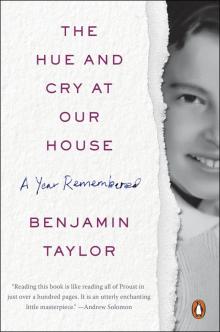

The Hue and Cry at Our House

The Hue and Cry at Our House