- Home

- Benjamin Taylor

Here We Are Page 2

Here We Are Read online

Page 2

I told him it was bleakness. The shine had gone out of everything. Strangulation in the viscera; no food seemed edible. Once or twice, to my shame, I’d gone to bed hoping a heart attack would finish me. In a word, I was ill.

Here was the sort of assignment Philip reveled in. He got me to his psychiatrist within twenty-four hours. “Tell him exactly what you told me. He’ll fix you up. Don’t tell him about how Momma burned the roast in ’57 and Daddy got so mad. He’s not that kind of doctor.” I had thought anxiety and depression were mutually exclusive. Our doctor told me they go together like Rogers and Astaire. He fixed me up with sertraline and olanzapine and may have saved my life. But the drugs have made me tearless. An odd side effect. At the Riverside Chapel, seated beside the dead man I adored, I found I could not cry.

I can’t be the first gay man to have been an older straight man’s mainstay. Philip had searched diligently for a beautiful young woman to see to him as Jane Eyre looked after old Mr. Rochester. What he got instead was me. The degree of attachment surprised us both. Were we lovers? Obviously not. Were we in love? Not exactly. Sufficient to say that ours was a conversation neither could have done without. Twelve years ago I saw him through his last love, for a young person less than half his age whose family strongly disapproved of the association and who evidently grew to disapprove of it herself. It was a trauma that might have plowed Philip under and that he tells aslant in Exit Ghost, the novel dedicated to me. After that came a couple of misguided attempts at courtship, painful for the women involved. Then he closed the door on erotic life altogether. He’d learned how to be an elderly gentleman who behaves correctly. He’d joined the ranks of the sexually abdicated.

I say: “I think I’ve worshipped at the altar of Eros long enough. I think my dues are paid.”

“Wait till you go well and truly to sleep where the body forks. A great peacefulness, yes. But it’s the harbinger of night. You’re left to browse back through the enticements and satisfactions and agonies that were your former vitality—when you were strong in the sexual magic.”

Why was the public so exceptionally interested in his personal life? E. L. Doctorow inspired no such curiosity. Neither has Alice Munro nor Toni Morrison nor Cormac McCarthy. Gossip about Cynthia Ozick is hard to come by. About Don DeLillo it is nil. Philip was something else altogether. True, Salinger comes to mind, chiefly because of the refusal to come out of hiding. Like Salinger, like Frost, like Hemingway, Philip generated a carapace that became a myth. In Frost’s case, it was the farmer poet. In Hemingway’s, the sportsman artist. In Salinger’s, the wrathful recluse determined to give his readers nothing more.

In Philip’s case, the Jewish good boy traduced by inner anarchy. Despite all the shifts and guises of fiction, it has been not so much protagonists as the man himself who, in book after book, keeps barging into the public eye, provoking adulation, hatred, learned commentary, everything but indifference. As with few other writers, readers have felt admitted to an inner sanctum they feel strongly about. At dinner one night in an Indian restaurant on Broadway, the actor Richard Thomas, spruce in a white beard, said to Philip: “You’re the writer who’s meant most to me.” (As I’ve had a case on Richard Thomas since he was John-Boy on The Waltons, the whole scene was heady.) Some variant of the encounter occurred when we went to any public place. Particularly on the Upper West Side. “Let’s have dinner on the East Side,” Philip would occasionally say. “Nobody knows me over there.” Prompt refutation came in a favorite eatery on Third when a woman at the bar beckoned to me with a long forefinger. “Young man, is that Philip Roth you’re with?” I nodded. She passed me her card. “Tell him I’ve got a classic six on Park and am available.”

Prior to the 1980s, he’d just been one of the interesting writers. Some of his books meant little to me—The Breast, for instance, which is lousy any way you look at it. But then came marvels like The Ghost Writer, The Counterlife, Operation Shylock and Sabbath’s Theater, proving him the best American novelist of his generation, our likeliest candidate for immortality. It was 1994, the year he finished Sabbath, that I met Philip. The occasion was our friend Joel Conarroe’s sixtieth birthday. The venue was the James Beard House on West Twelfth Street. There was Philip, aglow and triumphant: the dogged athlete who’d rebounded from orthopedic and mental breakdown, the natural bachelor who’d extracted himself from untenable marriage, the tenacious self-reinventor who’d written Sabbath, his most scandalous book.

That night he was all speed and laughter—head thrown back—and supernaturally quick with the next line. He asked what I’d been reading. I said Bellow’s Herzog. “Yes. That loaf of bread a rat has burrowed into, leaving his rat shape. Herzog cutting slices from the other end.” Then he quoted a line from memory: “‘But what do you want, Herzog?’ ‘But that’s just it—not a solitary thing. I am pretty well satisfied to be, to be just as it is willed, and for as long as I may remain in occupancy.’” Before leaving he said, “Let’s have lunch, kid”—but there was to be no lunch for years.

In the summer of 1998, after reading bound proofs of I Married a Communist, I decided to write to him. I was struck particularly by the final pages where the narrator, Nathan Zuckerman, recalls his mother telling him that Grandpa has died and is now a star. “I searched the sky and said, ‘Is he that one?’ and she said yes, and we went back inside and I fell asleep.” It makes sense anew to Nathan as an explanation of the dead, each of them a furnace burning away up there, “no longer impaled on their moment but dead and free of the traps set for them by their era.” No more calumny or betrayal. No more idealism or hope. Just the blazing heavens, “that universe into which error does not obtrude.”

A few days after I mailed my letter the phone rang. It was Philip wanting to talk. I felt at once that I was laughing with someone I knew well. Acrobatically unpredictable though the conversation was, I could follow his moves. Someone had to lead. Then he hung up without notice and I felt I’d been danced off the edge of the world.

Our first meal together, the first of hundreds, was three years after that. I’d moved back to New York full-time and he was there seasonally. We decided to have the long-delayed lunch. He’d sent me The Dying Animal and proposed that we talk about it. I met him at a Thai restaurant called Rain at Columbus and Eighty-Second. The neighborhood around the Museum of Natural History had already been Philip’s for more than twenty years.

“What do you think of my little book?”

Determined not to gush, I said that the scene where Consuela Castillo shows David Kepesh her doomed cancerous breasts reminded me of a similar scene in Solzhenitsyn’s Cancer Ward in which a girl, on the night before her mastectomy, goes to the room of a boy sick with a cancer of his own and chastely asks him to worship her doomed right breast. “Today it was a marvel. Tomorrow it would be in the trash bin,” I said, quoting Solzhenitsyn. In the silence that followed, I felt our friendship begin.

Early on he told me this: “What I care about is individuals enmeshed in some nexus of particulars. Philosophical generalization is completely alien to me—some other writer’s work. I’m a philosophical illiterate. All my brain power has to do with specificity, life’s proliferating minutiae. Wouldn’t know what to do with a general idea if it were hand-delivered. Would try to catch the FedEx man before he left the driveway. ‘Wrong address, pal! Big ideas? No, thanks!’”

I mentioned a few characters of his whose intense particularity touches the universal: Mickey Sabbath, Swede Levov, Coleman Silk.

“Glad for the vote of confidence but I aim only at specifics. Entirely for others to say whether some universal has been hit. I have for instance never—I repeat, never—written a word about women in general. This will come as news to my harshest critics but it’s true. Women, each one particular, appear in my books. But womankind is nowhere to be found.”

* * *

—

I’ve got an earworm, Ben.” Earworm: s

ome (usually idiotic) tune that won’t leave your head.

“There’s only one thing to drive out a worm and that’s another worm,” I say and sing, “Lydia, oh, Lydia, oh have you met Lydia, Lydia the tat-tooed lady!”

“I think that worked,” he says, shaking a finger in one ear. We’re on our way to Alice Tully Hall to hear the Emerson Quartet. They’re doing Shostakovich’s string quartets in a series of evenings. Tonight is the conclusion.

Philip loves the intimacy of chamber music. Orchestral and classical vocal are not for him. The one time I got him to enjoy an opera it was Shostakovich’s The Nose, hardly standard fare. Schoenberg’s Moses und Aron he refers to as Der Schmerz im Tuchas. He does allow as Strauss’s Four Last Songs are pretty good in the Schwarzkopf version. While he does not read music, he tends to grasp it in highly structural terms—exposition, development, reprise, et cetera—and has a remarkable musical memory, along with a quicksilver way of finding metaphors for what he’s heard: “The scherzo is four madmen making up a dance as they go.” “The cello is bearing a grudge.” “The second violin is more confidential than the first.”

Following intermission he is rigidly at attention for Shostakovich’s Thirteenth. The elaborate pizzicati and strange slapping of the viola belly with the bow stick fascinate us both, as if composer and performers were trying to get at something more elemental than music.

Afterward, out on Broadway, we listen to a bespectacled, wild-haired, Upper West Side–type boy of about fourteen expostulating with his father: “No, Dad, the violist has to climb into thirteenth position to play the unison note with the violins!” The unison note, if that’s what it’s called, was indeed a keening voice to send us home with. “How about that for a worm?” Philip asks. “Don’t think I’ll ever get it out of my brainpan.” Again he shakes a finger in his ear.

“Brainpan”: I go home and write that down. All of life up there in the brainpan, all of it somehow husbanded there. In old age, waiting for sleep, Philip would pick a year and revisit it month by month, week by week, room by room. “It’s all there. What happened is now the sum of me. A little patience and the locks turn. I’m back wherever I choose to go.”

My own locks turn and I am at Philip’s seventy-fourth birthday celebration. He’d said it would be tempting fate to hold out for seventy-five, so a seventy-fourth was planned at Judith Thurman’s town house. The garden was tented in and a marvelous supper laid on. Afterward Philip asked, rather surprisingly, if anyone cared to recite a poem from memory. Mark Strand reeled off one of his own (“In a field, I am the absence of field”), then looked at me as if to say, “Your serve.” What came to mind and I recited, stumbling only once or twice, was Frost’s “I Could Give All to Time” with its stirring conclusion:

I could give all to Time except—except

What I myself have held. But why declare

The things forbidden that while the Customs slept

I have crossed to Safety with? For I am There,

And what I would not part with I have kept.

“Those rhymes!” said Philip on the phone the following morning. “It’s as if nature made them.”

CHAPTER THREE

MISTAKES

A bread-and-butter note from Philip Guston

I ask if I may take a few notes. “You were saying about the Newark of the thirties.”

“It consisted of ethnic villages: Irish, Italian, Slav, Jewish. There was also a black neighborhood. And then, suddenly, it was December 7, 1941, and there was a current of feeling in all these villages that was stronger than what divided us. I think my sustained recollection dates from that afternoon. From then on, life became narrative rather than episodic. The onset of war was my starting point. I began to read the paper. The sound of Roosevelt’s or Hitler’s voice on the radio meant to me what it meant to the grown-ups, comfort or menace. And I remember understanding the fearsomeness of the banner headline CORREGIDOR FALLS, a shock to all my certainties. Home was safety. Home was bounty. I had no idea how little money we had, how few frills. I didn’t know what an artichoke was till I left home. When Mrs. William F. Buckley Jr. said to me, ‘What’s your background?’ I told her I didn’t have one, we were too poor. We enjoyed a lower-middle-class way of life and had won the elusive prize of family concord. The emotional spectrum ran from contentment to extreme happiness. That such a range is not your typical raw stuff for the making of a writer goes without saying. But it was my raw stuff. I’d been blessed with the luckiest of accidents. I was right, the family was right, the neighborhood was right, the guys up and down the street were right. ‘You’re a plum!’ my father used to say, meaning, ‘Do not fuck up this incomparable American opportunity life has handed you.’ Happy at home and happy at school. School was the other home. Chancellor Avenue School on the commercial street running perpendicular to Summit Avenue, three or four minutes from our doorstep, where so much of waking life was spent. My mother was for a few years president of the PTA and therefore knew all my teachers. I was surrounded by a female conspiracy devoted to my safekeeping. I ate up school like it was a smorgasbord, skipping half-grades as I went, which was how I came to be a college freshman at sixteen.”

“Writers,” I say, “can be sorted into school-lovers and school-haters, I’ve noticed. None are lukewarm about school.”

“School, not home, was where I found out about literature. We owned only four books: three novels by Sir Walter Scott and William L. Shirer’s Berlin Diary. My mother read bestsellers borrowed at one cent a day from the rental library of our pharmacy. Pearl Buck she adored. Also Louis Bromfield, a truly forgotten name. Nearby was the branch library where the rest of literature patiently waited. I filled my bicycle basket with whatever took my fancy. Adventure stories by Howard Pease. Sagas of early America by Howard Fast, laced with pro-Communist undertones lost on me. Then in high school came the lightning and thunder of Thomas Wolfe. I felt I was Eugene Gant, his hero. This was the necessary romanticism of extreme youth.”

I wonder whether Look Homeward, Angel and Of Time and the River were his genesis as a writer.

“Strange to say, I read those without a single thought that I too should write down in deathless lyrical prose the record of my exalted adventures. But I do think the very sensitive, very terrible stories I produced in college must have owed a lot to Wolfe. I remember also some reflections in verse on the falling of the first autumn leaf. I won’t be reading any of that juvenilia again to confirm my low opinion of it.”

But how did he get from there to the assurance of Goodbye, Columbus?

“I improved, though not out of all recognition. As you might expect your dentist to improve. Goodbye, Columbus is a happy-go-lucky book full of youthful, simple starts that are a vast improvement over the college efforts. In its defense I can say no more than that. Fortunately, I’d been schooled not just by Wolfe but by the Sunday-evening radio comedies: Fibber McGee and Molly, Fred Allen, Jack Benny. Whatever is good in my first book owes something to those masters.”

I ask about Letting Go and When She Was Good, which came next.

“Oh, I wanted to be literary, wanted to be influenced. There were Flaubert and Henry James. There were Dreiser and Sherwood Anderson. Under such spells I wrote those two gloomy novels, Letting Go and When She Was Good, for the second of which I have a soft spot even now. It’s got a genuine heroine, Lucy Nelson. But also a one-note depressiveness and no particular color. Some other writer could have written it.”

“What follows seems a bolt from the blue.”

“I discovered I was not a gloomy but a raucous talent. And that’s the story of Portnoy’s Complaint, in which I gleefully overthrew my literary education, shed the proprieties to reveal a Jew in all his libidinous tumult—and good taste be damned. People professionally worried about the public image of the Jews were naturally going to be cross. The freewheeling, farcical, ventriloquistic fun Bob Brustein, Al

Goldman, Jules Feiffer and I were having at dinner parties—our improvisational theater, you could call it—gave me the idea for a full-scale farce with which to answer the abominations of the time: assassinations, cities afire, the nightly news from Southeast Asia. I flung my harmless obscenities back at the world-historical ones. The book’s premise was simple: A young man in psychoanalysis is as trapped in a Jewish joke as was Gregor Samsa in the body of an insect, with lusts as repugnant to his conscience as his conscience is repugnant to his lusts. No wonder he can’t stop talking. ‘You want to hear everything, Spielvogel? I’m telling you everything.’ Did you ever read Bruno Bettelheim’s case notes in the voice of Dr. Spielvogel?”

“What?”

“He called it ‘Portnoy Psychoanalyzed.’ It’s what poor beleaguered Spielvogel writes down after the analytic hour is over and Portnoy has mercifully left. He reports that, from time to time, he’d love to reply to his sex-crazed babbler but can’t get a word in. Very doleful and funny.”

I ask if he knew how seismic the book would be.

“Early chapters excerpted in Esquire, Partisan Review and New American Review created strong commercial expectations and I received a quarter of a million dollars against royalties. A staggering sum back then. I remember taking my parents to lunch to prepare them for what was coming. I said newspaper and magazine and broadcast journalists were likely to contact them and that they should feel free to say thank you for calling and hang up. Years later my father told me that after that lunch my mother burst into tears saying, ‘Poor Philip is suffering from delusions of grandeur! He’s going to be so terribly let down!’”

I mention that he’d already had a taste of scandal when caught unawares by the response to “Defender of the Faith” when it appeared in The New Yorker. The accusation of giving aid and comfort to anti-Semites had stung him terribly. Rabbis in their pulpits had asked what could be done to silence such a man.

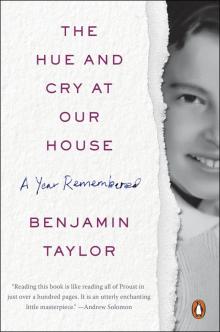

The Hue and Cry at Our House

The Hue and Cry at Our House